Gun lovers all over the world like lists of «best» gunmakers and love to argue who made a better gun. In Russia, for instance, there’s an unwritten rating of Belgian makers that affects a gun’s price tag along with other factors such as condition. I don’t know who compiled this rating and what criteria they used, but I know that its value is dubious. Belgian guns of the same class by different makers, on close inspection, usually turn out to have the same quality — if not prove to be the same gun. For example, let’s look at Brancquaert and Defourny.

Both Brancquaert and Defourny figure prominently on the list of the makers that Marco Nobili’s influential work identifies as equal to Lebeau-Courally. Other names on the list include E. Bernard, C. Braekers, Britte, J. Bury, A. Cordy, Dumoulin, A. Forgeron, A. Francotte, Browning, Galand, N. Lajot, Mahillon, ML, E. Masquelier, Pirotte, F. Thirifays, F. Thonon, J. Thonon. This alone would seem to imply that they were gunmakers of the same level. However, things go a little deeper than that.

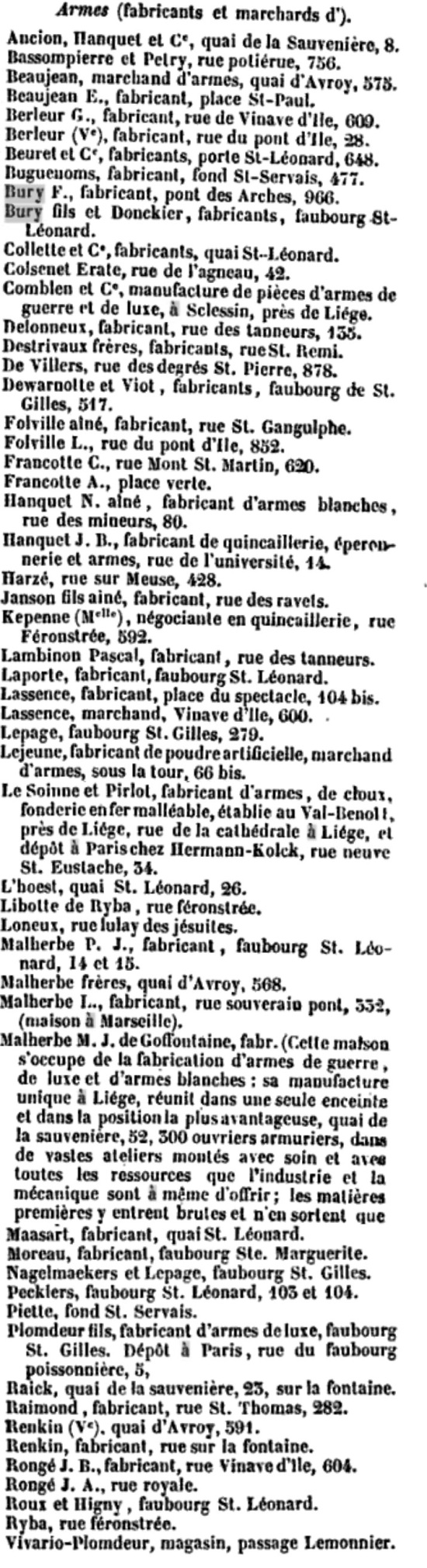

But let’s first look at the Liege gun trade at the turn of the XX century, when both Brancquaert and Deforuney entered the scene of best gunmaking. We can get answers for many questions from the account of Sergei Zybin, Head of the Repair and Hunting Guns Workshop of the Imperial Tula Arms Works, who was sent to Europe in 1902 to study progressive methods of making hunting guns (at least, this was the official version of his assignment). Zybin writes of Liege as a community of incalculable individual craftsmen, small shops and large, steam-powered factories, that worked together almost as a single body. There were businesses that managed to assemble large volume of guns without any sophisticated machinery, purchasing parts from more high-tech manufacturers. On the other hand, even Pieper, Liege’s biggest maker, had nearly all their guns finished by independent one-man shops.

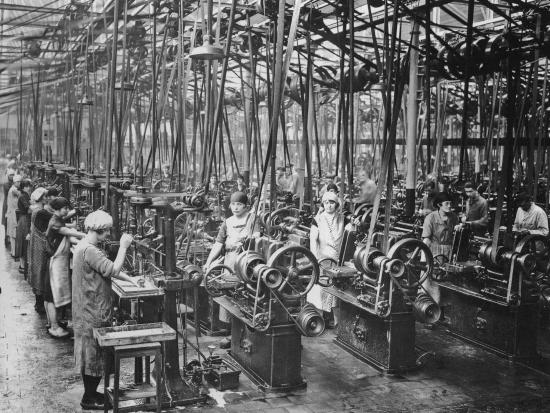

Wherever machinery could help, it was used — even individual craftsmen (or women: more than a third of the workforce was female on some firms) had access to steam-powered machines, with specialized businesses renting out shop floor space at affordable daily rates. Where machines couldn’t cut costs, the jobs were done by individuals at homes. Outsourcing secured the entrepreneur from strikes and such; on the other hand, self-employed craftsmen were better motivated and utilized their time and resources better. All of that fused into a flexible system that could produce any quantity of guns of every description cheaper than anywhere else.

Before the WWI, when the main Belgian gunmaking brands were only establishing themselves, some differences in quality could be observed, and some sort of ranking could be established. But the between-the-wars period all variation disappeared. The catalogue of H&D Folsom Arms, New York, listed over 200 various Belgian gunmakers they sold in the USA — but the valuators of American auction houses today treat all of them alike (with exceptions for Lebeau and Francotte). And, in a way, they are right — most if not all Belgian firms of the period ensured the same quality for the same money.

I don’t mean to say that there weren’t any artisans who were above the mass. Liege was home to a number of gunmaking stars. Hyppolite Corombelle, for example, the engraver par excellence, who later moved to Italy to become the founder of Bologna engraving school. But the names of the stars did not appear on the guns and remained unknown to the public. With the world’s economy struggling, all ambition gave way to the need to sell: under one’s own brand or some other name, complete guns or parts or some work on them, it didn’t matter.

Now that we got a glimpse on how Liege gun trade worked, let’s get back to the heroes of the story.

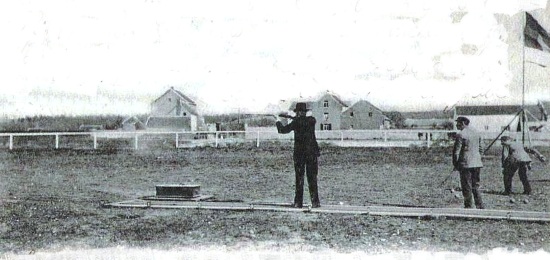

Front page of Brancquaert’s catalogue showing the Wellington live pigeon shooting grounds in Ostende.

Louis Brancquaert owned a gun shop at 202 Avenue de l’Hippodrome, Bruxelles, on the way to the Boitsfort Hippodrome not far from the shooting club «Tir du bois de la Cambre». Brancquaert sold hunting and pigeon shotguns, accessories, and Mullerite ammunition (made by Muller & Co, Liege), which was advertised as the best for live pigeon shooting. He also patterned and retailed «Brancquaert`s pigeon–trap» — a trapdoor cage for releasing birds for live pigeon shoots. The patent, however, was only a «brevete S.G.D.G» (see the article about Lebeau-Courally for what it means). Louis Brancquaert himself was an important figure in live pigeon shooting as shooter and acting as secretary of at least three shooting clubs: in Bruxelles («Tir du bois de la Cambre»), Spa and Ostende. Live pigeon shooting was an expensive hobby, and provided Brancquaert with connections in the top society.

In fact, Brancquaert’s fame as a gunmaker rested on live pigeon shooting. His name first caught the gunners’ eye in 1897, when Baron Raoul de Vriere, former Secretary of the Belgian Embassy in Washington, used a gun by Brancquaert to win the Grand Prix in Paris. By 1905 Brancquaert’s guns secured three gold medals, a silver cup and 30,317 Franc of prize money.

Brancquaert sold his wares all over Europe through a wide network of sales representatives: there were nine in Italy alone. His guns were of best quality only and with an option to place the customer’s monogram or crest on the trigger guard. Model 1 was a carbon copy of Purdey by Beesley’s Patent self-owner, and Model 2 copied the Holland&Holland sidelock. Model 3 was a side-plated Anson&Deeley boxlock with a single trigger; it was advertised as the company specialty, not inferior in any way to English guns of the same type. Model 4 was Model 3 with double triggers, Model 5 was a bar-action hammer gun, and Model 6 was Model 4 without side plates. Model 7 was a three-barreled gun, with two 12 or 16 gauge smooth barrels on top and a .450 Express below; it featured a patented cocking system and a rear sight that rose automatically when the selector was shifted to the rifled barrel and went down as the action was opened.

However, Brancqueart was never a gunmaker in the true sense of the word. It is not a secret that the guns he retailed were supplied to him by Defourny.

The Defourny dynasty of gunmakers was founded by Antoine Joseph Defourny (1805-1873). He had ten children, and his two elder sons Noël Joseph (1834-1918) and Gilles Joseph (1831-1915) became gunmakers too, while another son, Jean (1850-1914) was a gun trader. Like his father, Noël had ten children, however, three of them died in infancy. But two of his surviving sons, Antoine Joseph (born April 9, 1862, died August 19, 1943) and Alphonse (1870-1948) became gunmakers, and another son, Noël Victor Jean, was the State Weaponry Controller. Gilles Joseph’s family was less numerous, with «only» five children, and two of his sons, Guillaume (1865-1916) and Jules (1871-1958) also became gunmakers.

Guillaume Defourny worked for August Lebeau, and in 1896 opened his own business, G Defourny-Sevrin. This firm continued after his death for some time and closed in 1955. His son Georget (1900-1973) was a gun trader. Antoine Joseph Defourny Jr got married in 1891, and had seven children. Two of his sons, Joseph (1892-1976) and Noël (1897-1977) also became gunmakers. In 1895, Antoine Joseph Defourny started his first business of making «de luxe» firearms. He claimed 15 Belgian patents for various firearms improvements, but apparently never saw it necessary to protect his rights abroad. By contrast, his son Noël patented his single selective trigger (which he later fitted to many of his father’s over/unders, including the early Anson&Deeley models) first in Belgium (in 1949) and then in the USA (Patent № 2.639.972 of March 31, 1953). Antoine Joseph Defourny made a great contribution to the Belgian gun trade as an inventor. Especially valuable was his work on improving the Beesley self-opening scheme, to which I dedicated a separate chapter.

However, not all Defourny’s inventions were equally successful. An example of this is his over/under. Defourny’s first shotgun with one barrel on top of the other dates back to 1905, four years ahead of Robertson’s and Woodward’s famous patents. At the time, the over and under was still some sort of gunmakers’ terra incognita, and it shows in Defourny’s design. His decision to use the Anson&Deeley principle was justified by logic — however, it lead to complications. For instance, in order to house the cocking rods, the action frame had to have extremely thick walls. There was no room inside Defourny’s action for a normal sized striker for the under barrel. Consequently, the striker had to be very small, and its travel very short. That made it necessary to use an extremely powerful mainspring, which in turn caused quick wear of the parts.

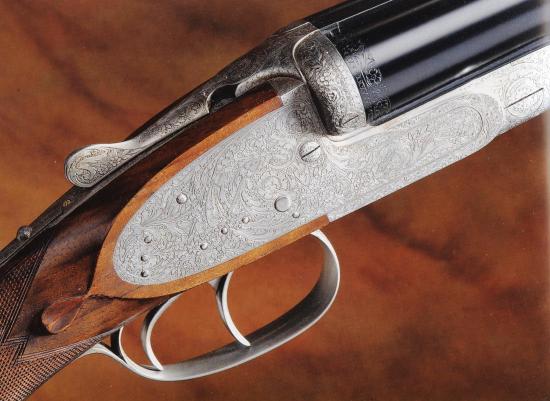

Later Defourny improved his design. He used Holland&Holland type bar action sidelocks, first conventional than hand-detachable; fitted the gun with ejectors; decreased the thickness of the action, giving the gun instantly recognizable look. On Defourny sidelock over/unders the self-opening effect is so significant that Holt’s experts classify them as assisted-opening. His uncompromising war against weight was a relative success: a 12 gauge Defourny over/under tips the scales at 3.1 kg; the barrels are 71 sm. long and weigh 1.45 kg. This was made possible by 18.2 bores, which ensured 150 gram weight reduction as compared to regular 18.5 mm bore.

Still, 25 years of improvement did not make the design truly successful. I believe the reason was that Defourny kept trying to build a side-by-side with stacked barrels. The schemas he used, the arrangement of parts, including the mutual location of the hinge pin, ejectors and cocking rods, followed old side-by-side patterns. In spite of that, Defourny’s over/unders had a widespread influence in Belgium, and were also built by other Belgian makers, including A. Francotte, (with whom Defourny had a joint patent for ejector cocking scheme «applicable to all weapons with tilting barrels») and Defourny-Sevrin.

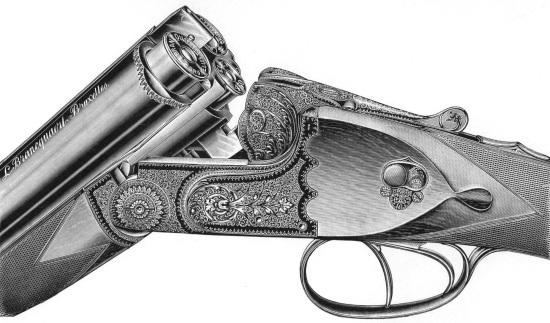

The strangest thing about Brancquaert and Defourny is that in all those years nobody ever wondered why guns from Brancquaert’s catalogues match the guns from Defourny’s catalogues to a T — even the drawings are the same! For example, Brancquaert’s Model 1 is Defourny’s Model 27 — while Defourny’s Model 1 is Brancquaert’s Model 7. In May 2008 Christie’s auctioned a Brancquaert gun which the auction’s experts identified as «assisted opening»; in the autumn of the same year that gun was auctioned again by Holt’s, this time the experts correctly attributed it «self-opening». From the description, it was clearly Defourny’s patented self-opening system.

My own Eurica! moment came when I got to see Brancquaert’s Model 8 over/under. Apparently, Brancquaert managed to supply the Royal Court of Spain with one, as the catalogue contains appropriate announcement, complete with an image of the Court’s crest. But no matter who owned it, Brancquaert’s Model 8 was the good old Defourny’s design and work.

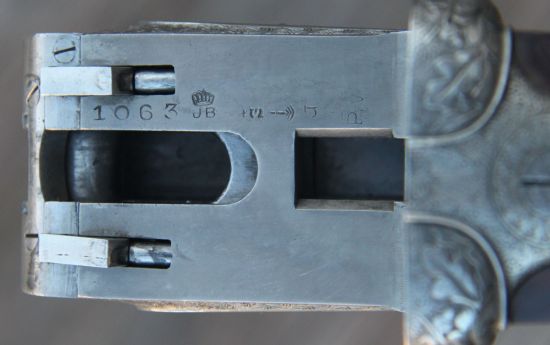

As a matter of fact, all Brancquaert’s guns known to me bear a Defourny stamp somewhere — sometimes on the action under the stock, sometimes in plain view on the barrel. Speaking of Defourny’s stamps, his «A.J.D. patent» does not signify that the mechanism in question or any part of it was Defourny’s invention. There is a subtle, but significant difference in meanings between the French words «brevete» (which means the same as the English «patented»), and «patente», which stands for permission to use a certain activity, duly paid for. Consequently, «A.J.D. patent» is only Defourny’s trade mark.

If you know where to look, you’ll find a Defourny stamp on ever Brancquaert gun — for example, on the inside of the action.

The same stamp from the shotgun assembled for Brancquaert by Joseph Defourny (Antoine Joseph Defourny`s son) in 1927. Brancquaert`s Model 1, Beesley-Purdey action. Photo: http://www.steniron.com

Apparently, Brancquaert, with his influence in live pigeon shooting world, was a godsend to the beginning gunmaker who only started his own shop at the age of 33 and at first did not build more than 15 guns a year. The irony was, however, that Defourny himself depended on the trade to fulfill Brancquaert’s orders.

It is highly unlikely that Defourny’s atelier had a considerable manufacturing capacity. His first shop was located in Herstal, on rue Petite Voie. After that, his address changed as many as seven times. Some of the moves could be in fact only changes in the numbering system on rue Nicolas Defrêcheux (consistently with this hypothesis, all rue Defrêcheux addresses are on the odd side of the street). But that doesn’t explain moving to Rue Champs de Foxhalle and Rue de Jupille. A manufacturing enterprise with heavy machinery necessary for full cycle gun production can hardly be expected to hop from place to place across the town every few years.

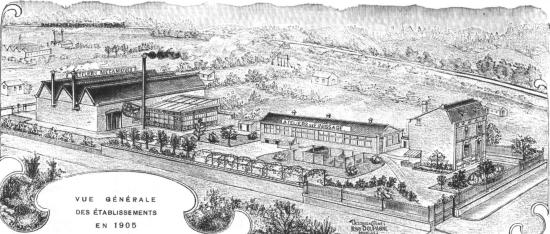

Another item of circumstantial evidence is a gravure from the 1938 catalogue, showing Defourny’s premises in 1905. Especially touching is the little detail of the small poultry yard, complete with the chicken, on the premises. The question is, at a time when every company that actually owned a factory proudly printed a photograph of it, why would Defourny use an obscure drawing instead? The building on the right rather closely resembles one of Defourny’s actual premises at rue Nicolas Defrêcheux, and the poultry yard is probably genuine — but the rest of the drawing, with smoking factory pipes and everything, looks more like a property development plan than reality.

The drawing from 1938 catalogue showing Defourny’s premises in 1905. Note the poultry yard in the middle.

«Depended on the trade» doesn’t imply that Defourny was not a «real» gunmaker. He obviously had a staff of artisans and performed at least some works in-house. A close study of the 1938 catalogue allows us to identify Defourny’s input to his guns precisely. On Model 1 it was all parts of the mechanism that were invented by Defourny, the rear sight and the side safety. On Model 2 — side locks and ejector; model 8 — the mechanism and ejector, on Model 19 — ejector, etc.

A contrast to Defourny’s drawing: Charles Sporcq catalogue showing a full inside view of the premises from shop floors to the store counter.

Defourny, just as most other small-scale makers, almost certainly never made action frames and barrel blocks, outsourcing them from bigger manufacturers such as Fabrique Nationale (FN). The evidence for this is that immediately after FN began to produce the sidelock with original cocking system, identified as «System Anson 1928» in the jubilee edition of the FN book, an identical gun appeared in Defourny’s model range. His over/unders were probably made in cooperation with A. Francotte & Co, which was a small, but a «real» full-cycle manufacture that could do everything in-house.

Many details of the cooperation between Defourny and Brancquaert remain unknown, but it was beyond doubt mutually beneficent, and probably ran deeper than making guns. In 1913, Defourny became a Knight of the Order of the Crown — a high award of Belgian Kingdom, and in 1928 the Officer of the Order; in the same year he was appointed the Representative of Belgian gunmaking industry at the Milano International Exhibition. There are ten degrees in the Order of the Crown, and the Knight and the Officer are the fifth and fourth. What was unusual in it was the fact that normally gunmakers were awarded for their input in the country’s defense. Antoine Joseph Defourny never had anything to do with military arms, never had any defense contracts, and never ever worked for the government. However, Brancqueart, through his involvement in live pigeon shooting circles, had enough connections in high society to get a friend of his knighted. This is only an unconfirmed guess, but it is not improbable.

Defourney O/U 20 gauge. Photo: http://www.pugsguns.com

So, this is far from the full story of Defourny and Brancqueart. But it shows the complicated relationship between various Belgian makers of the period, and demonstrates why all «lists» and «ratings» that place one Belgian gunmaker higher than another should be taken with a big grain of salt. I can imagine the confusion it all causes for beginning gun lovers and collectors. «Whom to believe?» they might ask in despair. To this I always say, don’t trust anyone except proof marks and official documents.